Just two weeks before the start of the new school year, Ilsur Khadiullin, the education and science minister of Russia’s Republic of Tatarstan, warned that the region faces a serious shortage of teachers.

“Much attention is paid in Tatarstan to the training of teachers and the development of professional skills,” Khadiullin told an August 13 meeting of educators in Layesh. “Nevertheless, for the coming academic year, there is a shortage of more than 2,000 teachers.”

The ministry’s website put the figure at “almost 2,300.”

The announcement came as no surprise to many educators in the region, who say low salaries and other unfavorable conditions are making teaching an increasingly unattractive profession.

“It is a well-known fact that salaries are low,” said one former teacher,* who left her school in the Tatar capital, Kazan, two years ago. “Young people can earn much more at other jobs. You can get 70,000-80,000 rubles ($765-875) a month as a courier.”

“If you get extra work at your school, you can get 30,000 ($325) or 40,000 ($440) — maximum 50,000 ($550),” she added. “But for this you have to work both day and night. There is no time to breathe.”

The woman said she loved her job as a teacher, but the overcrowded classrooms, onerous administrative duties, and low wages forced her to leave.

There are about 32,000 teachers in Tatarstan, according to government statistics. The average basic salary is reportedly 53,000 rubles ($580) a month. According to job advertisements studied by RFE/RL, actual starting salaries are even lower. About a third of teachers teach additional classes or take on other work at school to boost their take-home pay.

Participants in online chat groups for teachers and other educators in Tatarstan also highlight the problems of low pay and overwork.

“This problem can be solved very easily,” one teacher wrote on the VK social media site. “First, teaching should be the focus of the job. Free teachers from the huge amount of unnecessary paperwork. Second, the salary should be at least 100,000 rubles ($1,000).

The average age of a teacher in Tatarstan is about 48, according to republican government figures. Some 21 percent are under the age of 35.

Khadiullin said at the August meeting in Layesh that roughly 4,000 people graduate from the republic’s pedagogical universities and institutes each year, “but not all are employed by schools.”

“Staffing shortages remain a problem that has not been solved yet,” he conceded.

School budgets have been further stretched since the 2021 introduction of the Navigators of Childhood project, under which each school director must hire an “adviser” in charge of “vospitaniye,” a Russian term that denotes the process of raising and educating children with proper behavior for integration into adult society. The program has been seen as part of the state’s efforts to prevent youths from drifting into dissenting circles.

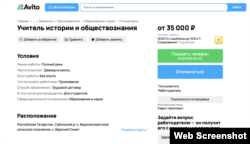

Schools have been pressing staff members to try to recruit acquaintances to fill the shortfall. In addition, announcements regularly appear on education-themed social-media chats. Ads seeking teachers have even appeared on Avito, a Russian classifieds site. Recently a rural Tatarstan school placed a notice there seeking a history and social-studies teacher for 35,000 rubles ($380) a month.

One school in Kazan has been placing primitive flyers seeking teachers in the entranceways to residential buildings.

In 2017, thousands of teachers in the republic were terminated when mandatory Tatar-language classes were dramatically reduced following complaints from ethnic-Russian residents of the region. President Vladimir Putin said at the time that it was “impermissible to force someone to learn a language that is not [their] mother tongue, as well as to reduce the hours of Russian-language [instruction] in Russia’s ethnic republics.”

In response to a recent online advertisement seeking Tatar-language teachers, one educator commented in a private chat on August 19: “First they fired them, and now they are trying to hire them back.”

Teacher shortages are a chronic problem across Russia, as well as in many other countries. Early in the 2023 school year, Russian Education Minister Tatyana Golikova said the nation faced a shortage of “nearly 11,000” educators.

Written by RFE/RL’s Robert Coalson based on reporting by RFE/RL’s Tatar-Bashkir Service

*EDITOR’S NOTE: Because the Russian government has designated RFE/RL an “undesirable organization,” RFE/RL conceals the identities of its sources in Russia to protect them from prosecution.